“Between Chaos and Order: A Deep Dive into Multidimensional Art”

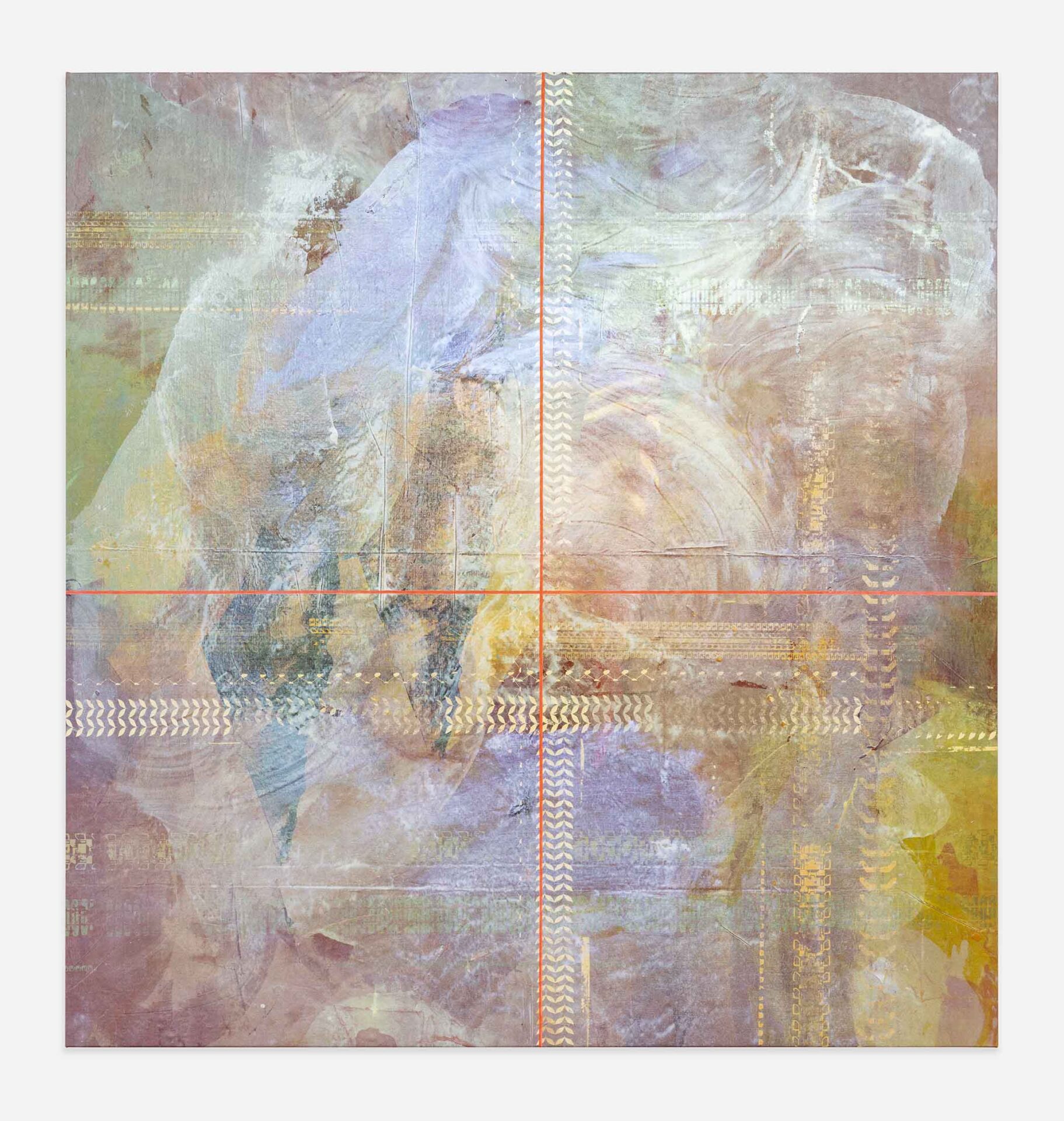

Mandy El-Sayegh, the acclaimed Malaysian-British artist, presented a captivating solo exhibition at Abu Dhabi Art with Lawrie Shabibi gallery. Known for her process-driven and multidisciplinary approach, El Sayegh showcased large-scale paintings and sculptural works that explored the intersections of materiality, language, and systems of order. For this presentation, she created an immersive in-situ installation, inviting audiences to engage with her layered, thought-provoking works that challenged and deconstructed bodily, linguistic, and political structures.

Following her recent exhibition in Abu Dhabi, our lifestyle editor, José Berrocoso, had the opportunity to speak with Mandy El Sayegh about her career and what lies ahead in her future projects.

Your exhibition in Abu Dhabi features your Reverse White Grounds series. Could you share how this series represents a shift or evolution in your exploration of the body and abstraction?

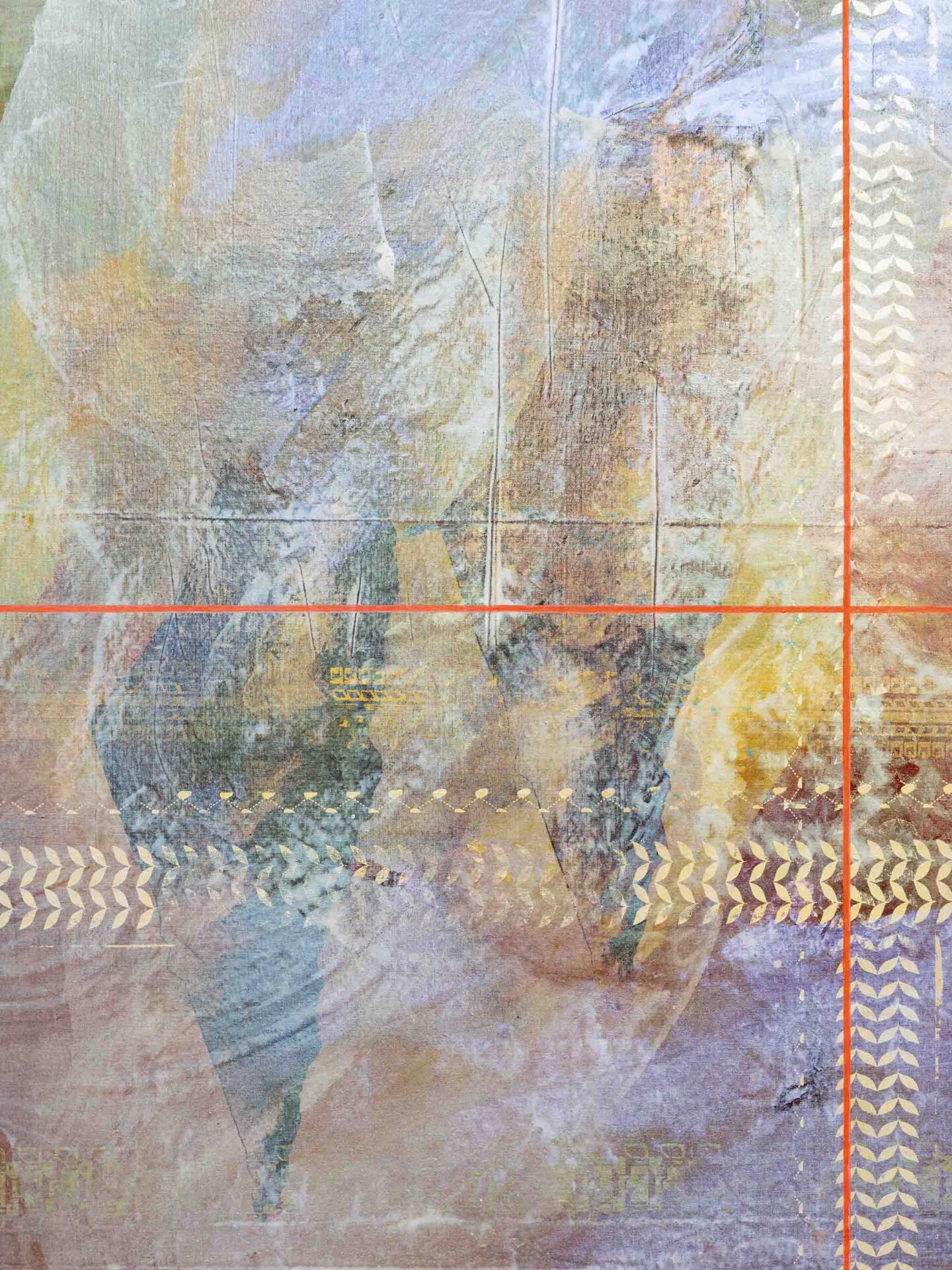

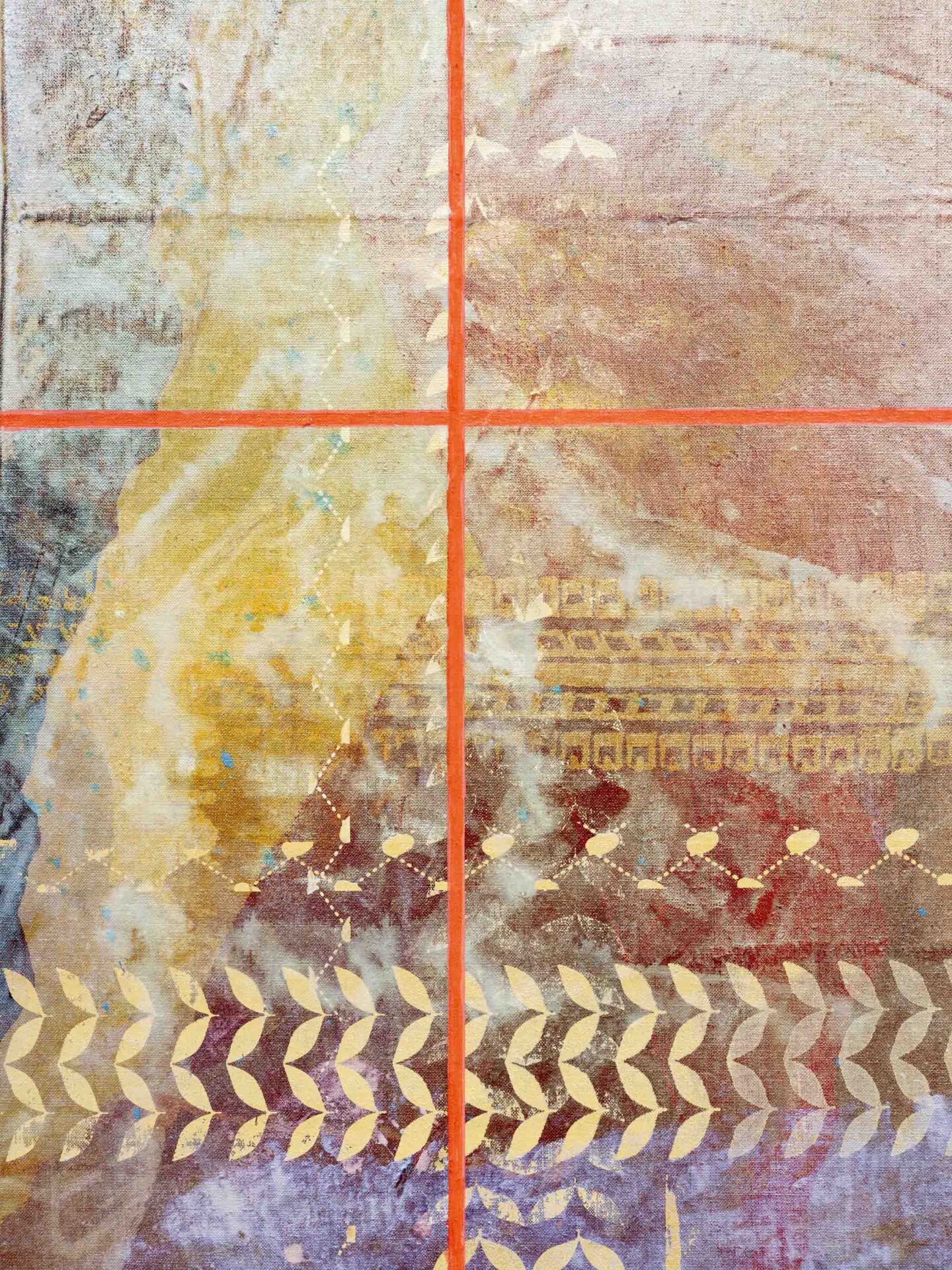

Reverse White Grounds builds on my White Grounds series, which are about exploring a white gesso surface, which I use to prime canvas or linen before other figurative elements are placed on top – the grid motif and collaged elements. This series is looking at historical sedimentation, the construction of whiteness ideologically across time and region, and questioning what constructing a foundation entails, through engaging with paint. The Reverse White Grounds series is an extension of that investigation – it is looking at a blood red primed surface which I have used more recently and using an iridescent layer to mute that primary base of wounding. The motifs that come on top of that surface explore the grid in broader terms – the crosshair; the keffiyeh pattern; the grid system; and how a map sits on that grid system; how the body is contained within these constrictions; how bodies, on a global scale, are organised in violent, constructed structures.

The concept of “bruising” in your paintings is powerful, symbolizing the emergence of deeper layers and hidden meanings. What inspired this idea, and how does it relate to your personal or artistic journey?

Bruising and wounding are explored through a palette of translucent layers. They are not hidden, rather they are composed on the surface. All the fragments within the works are still visible under close scrutiny, and only from certain distances is there a unification achieved through a grid, which holds that together, or a layer that is ‘lotioned’ on top. I am very inspired by the studies of flesh and its transparency and how, from a far you have an opaque colour, and upon closer inspection you see layers: the veins, the capillaries, the bruising. I am thinking about historical processes through this methodology.

In Just to state (2024), you use medical instruments and objects from your personal archive. Could you elaborate on how you see these objects influencing the viewer’s perception of the body and systems of control?

The vitrine tables I make are based on a type of methodology used in psychoanalysis, which is the engagement in free association. The patient is allowed to wander freely in their speech to reveal unconscious narratives. In Just to state, written with ‘to’, there is a double meaning, thinking about the phrase ‘two-state solution,’ for example. In the table we have fragments of a painting which contains silkscreened continents. So, I am thinking about the idea of saying, being able to express things through aesthetics, where censorship is very present in the climate, and finding modes of doing this materially, for example in the use of the double entendre. The objects are from my personal archive. They are often objects that I allow to accumulate in the studio, and I pick them intuitively when I am building a composition, similarly to how I make a painting. Meanings appear retroactively – giving the work a title is the last thing.

I can’t influence someone’s associations with these particular objects – while I have a very particular relation to them. But depending on where they sit – in what region, what time, and in relation to my practice, I guess that is how those connections are built. A lot of the materials in the work refer to commerce, art auctions, movement of bodies versus movement of goods, and luxury lifestyle versus ‘bare life’. A gold bikini alongside medical equipment.

Your work explores the intersection between anatomy and political systems, where bodily forms merge with maps and grids. How do these visual metaphors help you comment on structures of power and authority?

As I said in my previous answer, I don’t see myself as having the agency to influence people’s perceptions, but it is through free-association, collection, material association, and using the methods of psychoanalysis with material that I am trying to make connections between these dual realities that are often sitting parallel to each other at any given time.

Your pieces often confront systems of order, whether bodily or political. How do you see your work engaging with current global conversations around identity, borders, and governance?

This is such a complex and layered question I am not sure how to answer it. As an artist, these things are woven into my practice in such a multitude of ways. I don’t have particular answers to these questions, but art-making is my way of navigating the world and surviving. I metabolise fragments that deal with these issues, for example mapping systems, language and new media, and I bring elements of my own archive into that.

You’ve described your practice as an investigation into the breakdown of systems. How do you maintain a balance between chaos and structure in your work, particularly in the creation of your densely layered paintings?

Every body of work has something in common, which is that is has some ‘binding device.’ For the floor pieces and the ‘skins’ I make, that biding agent is latex. There must be something to hold the chaos, the fragments and the shrapnel of history in a matrix. Another device to do this is the grid – the painted or silkscreened I use in painting, to hold, again, the unevenness of ground together into a unified field, from a distance.

Could you talk about how your background—growing up in Malaysia and now living in London—has shaped your exploration of political and bodily systems in your work?

My mother wanted me to be born in Malaysia to avoid passport issues, but she swiftly returned with me back to her work in Sharjah and we lived there until I was six, and then moved to London. I spent a lot of my teens to early 20s going to Malaysia with family during the summers. This has definitely affected by vantage point and perception of the systems I am exploring and how my subjectivity intersects with different regions, and how privilege shifts across these movements.

With this exhibition in Abu Dhabi, what do you hope the audience takes away from your exploration of body, space, and power dynamics?

It is an expository practice, in that I am not actively stating a position, more showing the multiple layers and dual realities of existence across different regions of the globe, and how this is an uneven ground – whether that is explored through painting, or in the free-association in the table vitrines, or even in the news pages that are collected and assembled on the walls, which often quite starkly show those dual realities: commerce and destruction; luxury and duress.

How do you see your work evolving in future projects? Are there any new themes or materials you are eager to explore?

I have been increasingly engaged in performance elements, and video-making to activate the spaces of installations and create more of a live element to my work. This has been evolving over a number of years. I have always been interested in looking at solidarity movements and commonalities across time, of forms resistance that come up in these movements.

https://www.instagram.com/mandyelsayegh/

Photos: Abtin Eshraghi