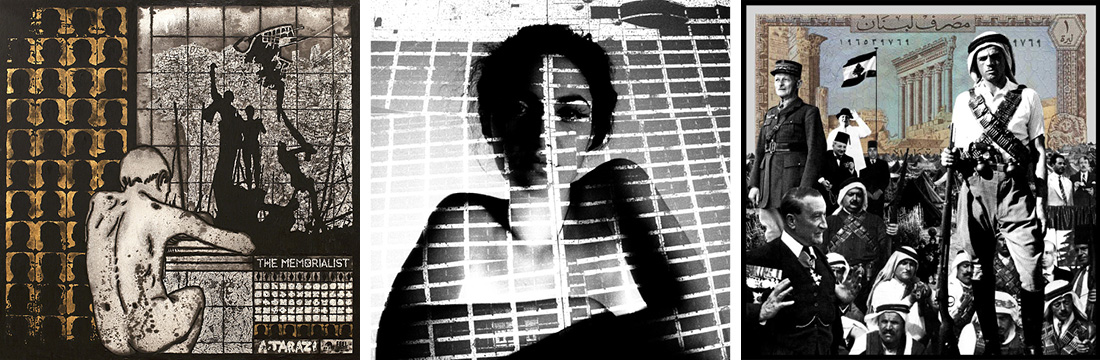

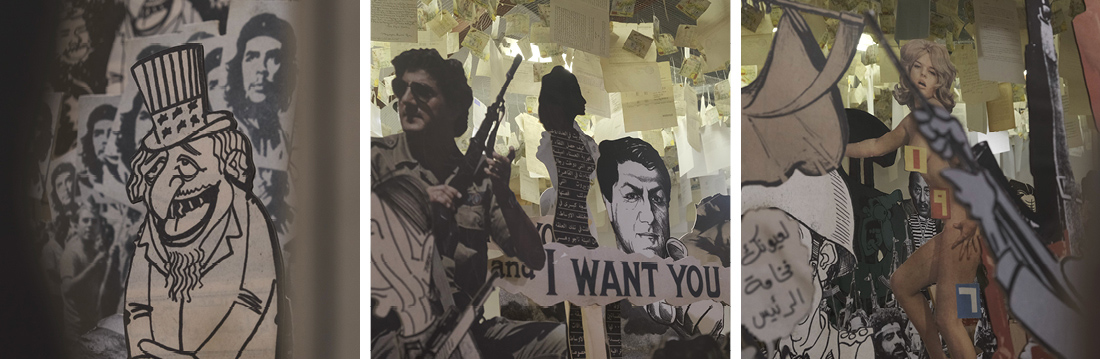

Born in Beirut in 1980, Alfred Tarazi is an artist whose practice defies categorization—one that traverses painting, sculpture, digital collage, installation, and photography with a singular mission: to dissect and reconstruct the complex layers of Lebanese history. A graduate in graphic design from the American University of Beirut, and later a resident at Krinzinger Projekte in Vienna, Tarazi has carved a unique path in the international art world. His work, often exhibited in major European institutions, is a visceral excavation of memory, identity, and trauma—especially those rooted in the unresolved legacy of the Lebanese Civil War. With an approach that fuses merciless realism with poetic fiction, he navigates the fractured terrain between historiography and imagination, using art as both a scalpel and a salve.

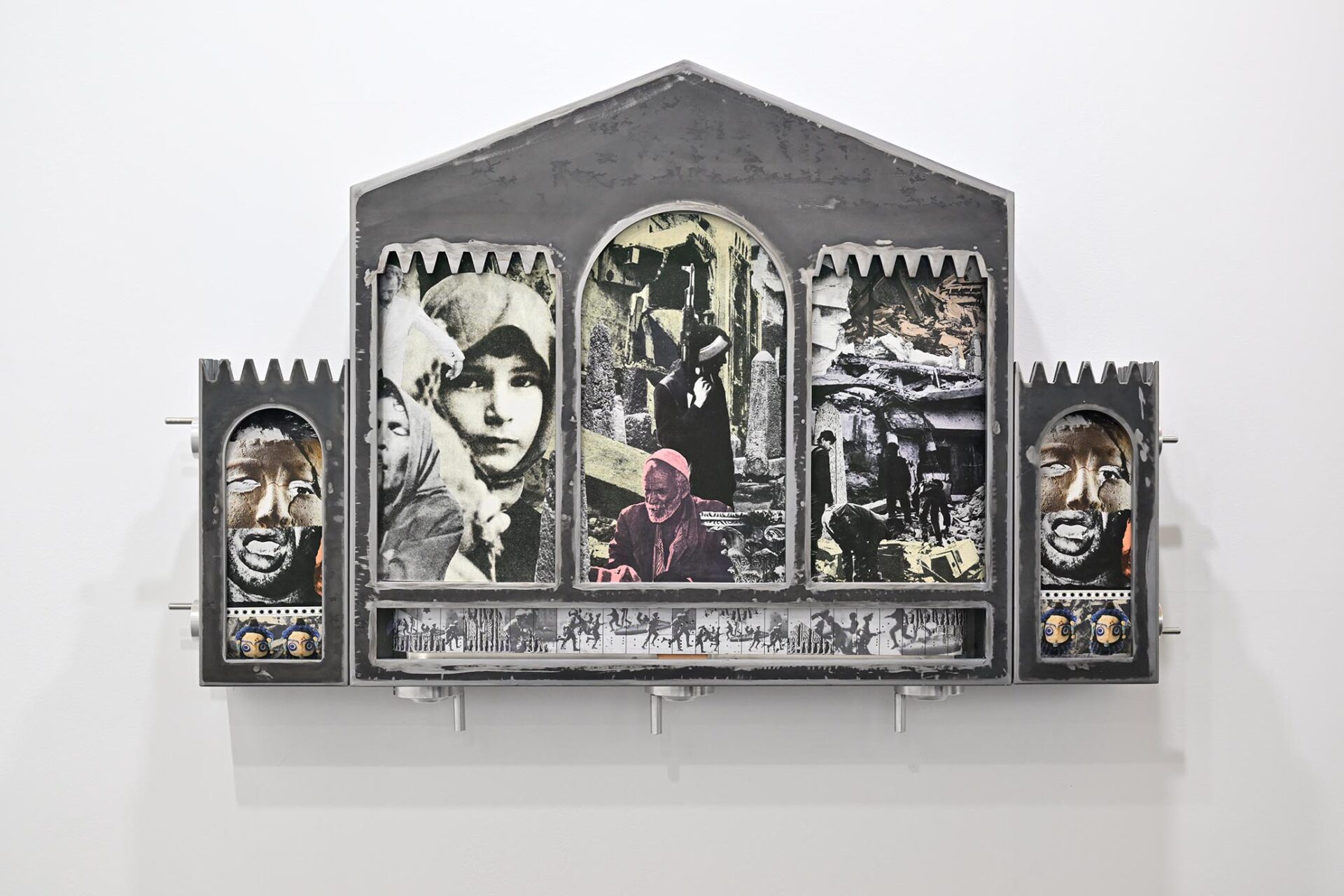

Tarazi’s latest exhibition, currently on view at the National Museum of Beirut, is perhaps his most intimate and ambitious to date. Drawing on a vast archive of objects inherited from his family—craftsmen and antique dealers across five generations—he creates a monumental installation that blurs the lines between personal mourning and national memory. Titled Hymn to Love, the show transforms doors, lamps, soap boxes, and forgotten relics into vessels of meaning, loaded with histories both monumental and mundane. In doing so, Tarazi interrogates not only the fragility of heritage in a region shaped by conflict, but also the role of art in preserving what institutional memory often neglects: the silent, fragmentary beauty of what remains.

José Berrocoso, our Lifestyle Editor, sits down with Alfred Tarazi to delve into the inspirations, narratives, and complexities behind his evocative body of work.

You’ve had a diverse and impressive career, with work spanning multiple disciplines such as painting, sculpture, film, and photography. What originally drew you to such a broad range of mediums?

Alfred Tarazi: If we consider that the medium is the message, then switching mediums is a concrete way of conveying different messages. I’m particularly drawn to the diverse methods one can use to create an image. Our history at image making is tens of thousands of years old. We have all this experience and history to find inspiration, and as practitioners, to create. One of my favorite modes of expression is perhaps sculpture. Currently I am working on my first film. Drawing remains the greatest challenge, with still a great learning curve ahead. Every medium is ultimately an opportunity to learn more about yourself and about the world.

Your work often revolves around complex historical narratives, particularly the intersection of fiction and historiography. How do you balance these two elements in your practice?

Most histories are fictions in their own self. Some fictions are better historical accounts than historical references. What binds both are the modalities used in production, through text and images. The role of fiction is to help us understand that our world is a construct that requires us to always put in into question. History books are therefore not as much accounts of things that have happened in the past but guidebooks for the future. I am always in the search of elements, sources and information that can help me understand the complexity of our relations with each other and the universe at large.

Your current exhibition at the National Museum of Beirut is deeply tied to the theme of memory and identity. Can you tell us more about how the objects from Maison Tarazi, passed down through generations, inform this exploration?

I come from a family of craftsmen and antique dealers through 5 generations. What results is a formidable and perhaps worrisome accumulation of objects and know hows. That activity was however interrupted in the middle of the Lebanese Civil War. Since then, with the door of a warehouse sealed as if it was the tomb of some forlorn pharaoh, these objects have been patiently gathering dust. I was only able to access this warehouse in the urgency of loss. Having abandoned the realm of commerce, the objects presented themselves to me with the ultimate vulnerability of capricious fragments demanding to be rescued. They gave me the multiple functions of guardian, archeologist and constructor. What else can I do but use these fragments and build with them? The installation at the National Museum is the third iteration, or third experiment at constructing with these. I hope there will be many others. I would also like to ultimately relegate all these objects to a museum.

The exhibition seems to explore a profound connection between your family’s history as artisans and merchants and the broader history of Lebanon and the Middle East. How did your personal family history shape the direction of this work.

The interesting thing about merchants, and perhaps the history of Kuwait amongst others attests to it, is that they form bridges across cultures and geographies. My family in the mid 1800s saw the appeal that oriental artefacts had on westerners visiting the region and they catered to this market. What role do artefacts play in history? A door, for instance, can serve as a frame. What happens in that frame throughout the centuries, that is history. There is a miniature door present in the exhibition which is a scaled model of the door of the French residence in Beirut. It is the work of my great grandfather Gebran Tarazi and was made in 1914 to be presented to the client who commissioned him to do all the woodwork for the edifice. In 1920, General Gouraud proclaimed the creation of Greater Lebanon in front of that door. This intersection highlights how the objects we produce embody our histories. Our world is loaded with meaning. However, that miniature door was forgotten in a warehouse about to be discarded.

The installation includes pieces from your family’s collection, such as Damascene doors, soap boxes, and lamps. How do these objects, traditionally viewed as decorative or commercial, take on new meaning in your exhibition?

I view all of the material passed on in my family as an incredible repository of geometry. An endless alphabet of lines and volumes that has, irrespective of function, a clear and distinct message: how do we translate the world and its beauty in objects that we produce. They are first and foremost a celebration of beauty. There is an interesting differentiation between what we consider decorative arts or fine arts. This, of course, is a separation determined by the west. I think in the Orient at large that distinction is less present.

At the heart of your exhibition is a rotunda dedicated to your mother, Renata Ortali, and an empty chair for your father, Georges Tarazi. What do these symbols represent to you personally, and how do they relate to the broader themes of memory and legacy in the show?

It is a precious opportunity one is given to honor one’s parents’ memory. It is a moment I desired and worked towards, but I was finally gifted to me by the director of Bema Juliana Khalaf when she was commissioned with the curator Clemence Cottard to organize the opening show of the Nuhad Said Pavilion for culture. In the exhibition there are two moments consecrating my parents’ departure from this life. The only reason to share such an intimate and emotionally loaded moment is to reflect communally on notions of loss. To reflect on life, on time, on how we translate time into objects and how these objects if disregarded can disappear, leaving no trace of our existence behind.

The concept of ‘Hymn to Love’ is central to the exhibition. Could you elaborate on what this phrase means to you, especially in the context of your exploration of craftsmanship, art, and materials?

Hymne a L’amour, or Nasheed el Hobb, has been a difficult title, yet the only one I could hold on to for this exhibition. Although it does not reference it, people might think of the Edith Piaff song, which actually ends with this sentence: God reunites those who love each other in the end. Which in the context of me reuniting my parents in the National Museum of Beirut completely applies. However, my main reference is to materiality and to all the love vested into shaping wood and copper. Crafts are by essence very slow and patient disciplines. They are a negotiation with materials through time. Their essence is love vested into matter to create beauty. The hymn I am speaking of, if we are talking in terms of sound, is of a hammer, slowly shaping and incising copper or wood, that sound is my hymn to love.

This exhibition addresses the fragility of heritage and the importance of institutional recognition. How do you view the role of contemporary art in preserving and questioning history, particularly in regions that have faced upheaval, like Lebanon?

What is interesting about contemporary art is that as an artist you get to set your own rules. So, while my father could have never dreamt of presenting his family’s legacy in the National Museum, as an artist, I was able to contextualize these objects within a contemporary gesture that allowed me to do that intervention. The life of an artist can however often be precarious. So, we can in no way replace or even compete with the necessity of having institutions to shelter and protect cultural legacies for generations to come.

The exhibition also touches on the idea of objects as ‘memorials.’ How do you see the role of everyday objects in shaping collective memory and history, especially in the context of a country like Lebanon, which has such a complex past?

How can we explain the emotional response we have to objects? From a priceless work of art to a discarded packaging reminiscent of our youth? What links both are the emotions they generate. Emotions come from intent, from the craft, the shapes and colors embedded in materials. A can of Tatra or Nido powder milk can tell us a lot about the Lebanese Civil War. Can one of those empty cans be a memorial for that war? What this indicates is how objects can be embedded with emotions. The only danger rests when in the urgency of life, objects, from the most mundane to precious ones can wind up in the mountains of trash humans produce on a daily basis.

In your artistic practice, how do you manage the tension between representing history faithfully and introducing imaginative elements? Is there a conscious effort to blur the lines between historical fact and artistic fiction?

In truth, reality with all its complexity and layers of history surpasses fiction. Imagination cannot overtake reality. But it can present simplifications and abstractions that render it understandable and relatable. With time, reflecting on the issue of representation and history I began understanding new notions about the agency of images in history. What if images, more than a tool of representation, are in fact active agents in history?

Looking back at your past exhibitions, such as your work presented at the Venice Biennale of Architecture and the Marrakech Biennale, how do you feel your practice has evolved? Are there certain thematic constants that have remained at the core of your work?

What binds all my projects are historical interrogations. As such every art piece, installation, film…is an opportunity of learning. History is such a malleable matter, a construct of information. However, history when conferred to the artistic realm goes way beyond information. History in the realm of art seeks to perturb, question, transgress. It is there to challenge dominant discourses and connect us to some level of truth.

Lastly, what do you hope visitors take away from this exhibition? Is there a particular message you’d like to convey about the relationship between heritage, memory, and identity?

The exhibition aims to create a point of rapture, a unique opportunity to reconnect with a heritage and a past that has been occulted by war and violence. Do we need to have an excuse to celebrate beauty? Do we need an excuse to speak across the ages and celebrate cultures passed on through generations? The present is relentless, the future uncertain and the past is this incredible repository of knowledge accumulated by our fathers and forefathers. What we, the living, safeguard of the past for future generations is not a question pertaining to the past, but to the future itself.